As an explorer of the water world, there is nothing I love more than finding a beautiful lake and going for a swim or a dive. I’ll picnic by the water and revel in the discovery of a sweet berry patch on a warm summer day. Wild blueberries contain the energy of the sun. They make me feel powerful. Here in this Treaty 11 Territory of Canada, the traditional territory of the Akaitcho and Tlicho Agreement People, the Native Dene describe at least 10,000 years of history. Their connection to the land is undeniable. On first inspection, this place looks like heaven to a lover of the outdoor world. But neither the Dene people or I will ever enjoy a relaxing swim or the luxury of eating the bountiful berries in the area. Arsenic, unfortunately, poisons everything in such high concentrations that it is not safe to swim in or drink from many of the lakes or eat the bounty of the land. It will never be safe here. Beneath the ground around Yellowknife, a monster is lurking. There is enough arsenic trioxide dust to kill every human on earth several times over. The Dene and the citizens of the region have been left with an enormous responsibility to stabilize the abandoned Giant Mine here and ensure that their descendants do not forget about keeping the monster shackled, 250 feet beneath the surface.

As an explorer of the water world, there is nothing I love more than finding a beautiful lake and going for a swim or a dive. I’ll picnic by the water and revel in the discovery of a sweet berry patch on a warm summer day. Wild blueberries contain the energy of the sun. They make me feel powerful. Here in this Treaty 11 Territory of Canada, the traditional territory of the Akaitcho and Tlicho Agreement People, the Native Dene describe at least 10,000 years of history. Their connection to the land is undeniable. On first inspection, this place looks like heaven to a lover of the outdoor world. But neither the Dene people or I will ever enjoy a relaxing swim or the luxury of eating the bountiful berries in the area. Arsenic, unfortunately, poisons everything in such high concentrations that it is not safe to swim in or drink from many of the lakes or eat the bounty of the land. It will never be safe here. Beneath the ground around Yellowknife, a monster is lurking. There is enough arsenic trioxide dust to kill every human on earth several times over. The Dene and the citizens of the region have been left with an enormous responsibility to stabilize the abandoned Giant Mine here and ensure that their descendants do not forget about keeping the monster shackled, 250 feet beneath the surface.

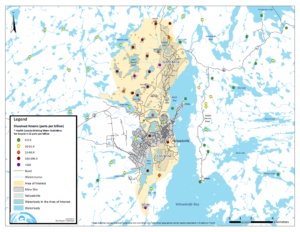

From 1948 until 1999, the owners of Giant Mine recovered 7 million ounces of gold making a profit of over 1.1 billion dollars. To release the gold from the rock they used a technique called roasting. The stone was ground to a powder and heated to melt the gold. Arsenic was released in toxic clouds over the land and lakes to the west of the mine. The arsenic trioxide rained from the clouds since it is highly soluble, odorless and tasteless. A current health study is underway to determine how many people’s lives are affected by the contamination today.

There is plenty to read about current clean up efforts, though it is hard to call something a “clean up,” when it is more of an attempt to stabilize a disaster in perpetuity. It is simply not possible to remediate the area. It will never be restored. The 100 buildings, tailings ponds, and especially the 237 tons of arsenic trioxide have to be sealed up entirely since water is so good at dissolving and moving the poisons back into public contact. The current plan, called the Frozen Block Method (which will cost more than the value of all the gold ever recovered) is to seal the underground arsenic trioxide inside a ten-meter thick ice wall which will need to be powered and maintained forever. And that is just the beginning. The tailings ponds must be sealed. Water treatment must be continuous, and inspections will have to be guaranteed for eternity.

There is plenty to read about current clean up efforts, though it is hard to call something a “clean up,” when it is more of an attempt to stabilize a disaster in perpetuity. It is simply not possible to remediate the area. It will never be restored. The 100 buildings, tailings ponds, and especially the 237 tons of arsenic trioxide have to be sealed up entirely since water is so good at dissolving and moving the poisons back into public contact. The current plan, called the Frozen Block Method (which will cost more than the value of all the gold ever recovered) is to seal the underground arsenic trioxide inside a ten-meter thick ice wall which will need to be powered and maintained forever. And that is just the beginning. The tailings ponds must be sealed. Water treatment must be continuous, and inspections will have to be guaranteed for eternity.

The Dene people and their storytelling tradition will have an important role moving forward at this constant care area. Using their traditional practices, they will craft a story about the monster underground and ensure that all future generations do not forget about the legacy of poisons that will not dissipate. They have to tell their children and their children’s’ grandchildren that the water is not safe and that the berries will always be poisoned.

The Dene people and their storytelling tradition will have an important role moving forward at this constant care area. Using their traditional practices, they will craft a story about the monster underground and ensure that all future generations do not forget about the legacy of poisons that will not dissipate. They have to tell their children and their children’s’ grandchildren that the water is not safe and that the berries will always be poisoned.

In 1999 after the mine declared bankruptcy, the Canadian government assumed responsibility for it. There are about 22,000 contaminated sites in Canada.