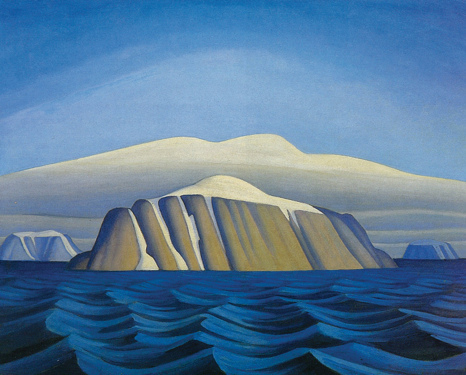

In 1931, famed Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris painted a series of canvases of Arctic landscapes that captivated the attention of Canadians. Landscape Photography of the time was either monochromatic or hand-painted in a pastel wash of color. It was Harris who brought the North to life in vibrant graphic brush strokes. His paintings of Bylot and Baffin Islands were some of the earliest representations that helped people build a visual impression of the mysterious wilderness of the Arctic. While studying his work in art school, my mind often wandered. Would I ever have the chance to experience the purity of such an incredible place?

Now standing at the very location that captivated Harris’ imagination, I am awed by the majesty of the snow-covered peaks, whose glaciers connect with the sea ice in Eclipse Sound. Misty clouds pour down the valleys in swirling masses of white that blend into the tableau before me. I can see that the connection of people, snow, mountains… the environment of the Arctic is one harmonious organism. The Inuit call the sea ice “ The Land,” and when they are out on the land, you can sense a palpable joy that animates their day.

I have been drawn to this place to share a story of ice. Elder Sheatie Tagak tells me that the time they have on the land is limited these days. He recalls that the sea ice used to set earlier, spread farther, and last longer. Now he waits until February for the ice to harden enough for his Skidoo and notes that the turning point, when the sea begins to melt, now comes in March. He also sees running water all year long. It is bleeding into town from beneath the glaciers and snow cover. The fresh water vaporizes from streaming rivulets that furrow the muddy road and pour down into the sea. Things are changing, and he and his people are trying to adapt.

Nobody can predict with certainty when the Arctic sea ice will be gone, but scientists agree that we are on a precarious downward slope. Professor Jason Box, a glaciologist with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland declares that “the loss of nearly all Arctic sea ice in late summer is inevitable.”

I feel compelled to document this rapidly changing landscape both above, below and within the ice. During my “Arctic on the Edge” project, I will be following the journey of ice from glacier calving grounds in Greenland, across Baffin Bay and down the coasts of Baffin Island, Labrador, and Newfoundland, where large bergs finally melt into the ocean. I’ll be sharing stories of shifting baselines, transforming geography and societal impacts of our warming world.

Camping on the sea ice at a place the Inuit call Kuururjuat, I recognize I may be one of the last people to have this opportunity. In just a few days, the ice is breaking up into increasingly large leads. The hard surface transforms into melting pools of turquoise blue, and the floe edge creeps ever closer. What will happen to the traditional hunt that unites families in their most treasured time together? What will happen to the polar bear, ring seals, narwhals and eider ducks? When I ask Sheatie Tagak about the melting ice, he laments, “it is happening, and we can’t stop it.”

Top: Inuit guide Kevin Enook pulls the kamootik over Eclipse Sound. Lower: Lawren Harris painting of the same region of Eclipse Sound and Bylot Island.